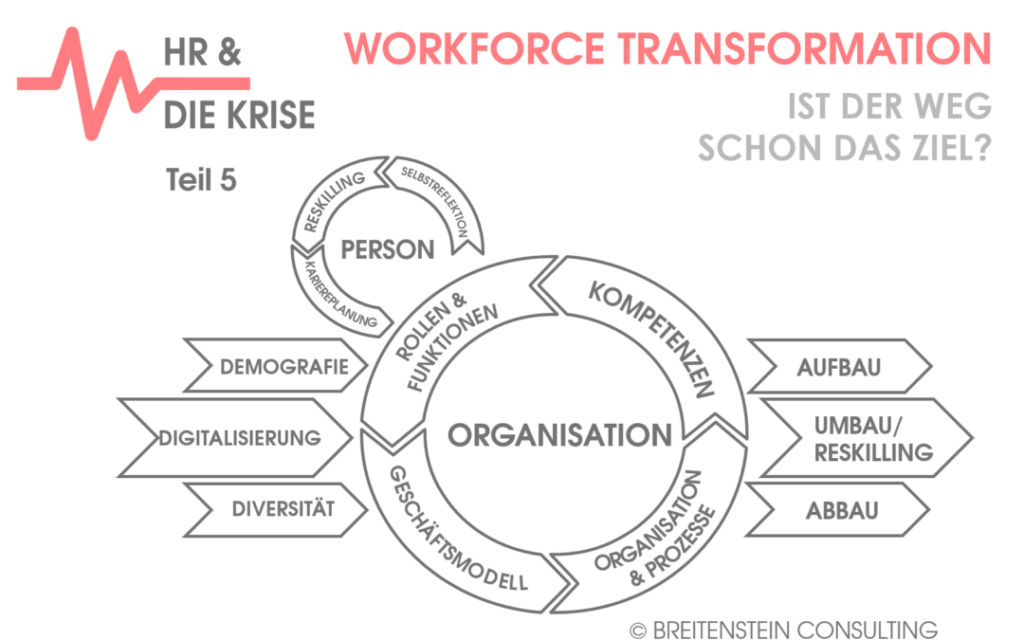

Workforce transformation has been the most discussed topic in the HR community for years. The coronavirus pandemic has only accelerated this. How much workforce expansion, contraction and restructuring is needed due to digitalization, for example, and where exactly? We have gained some important insights from specific projects and I would like to share them here. What are promising approaches? What are the risks in such projects? What can be derived from this for specific projects?

Workforce transformation in its original form – a brief practical report:

A brief practical report from 2005 (slightly adapted for reasons of confidentiality):

At the time, we had a business that provided desktop remote services. These were people who physically came to the workplace and set up a computer, installed software or repaired it. At the time, it was still a lucrative business. But even then it was clear that it wouldn’t be for much longer: remote service (where a technician connects to a computer virtually) had already been invented and software as a service (SaaS) and cloud computing were already on the horizon. So the management faced a dilemma: ‚If we get out now and sell, we will still get money for a profitable business, but we will lose customer contacts. And we will give away good employees. If we give it up too late, we will have expensive employees with outdated skills in outdated jobs that we will have to cut. Who knows if we can retrain them all and how many of them we will really need with which skills?

So the solution is: ‚We develop one or more future scenarios for the ramp-up of the new business and look at what impact this will have on the individual jobs and how we can then gradually restructure the team.‘ So it’s that simple?

On closer inspection, a number of detailed questions arose:

1. Timing: When exactly will which technical innovation establish itself in the market?

2. Scenarios: What would the time frame for implementing the change to our business model look like?

3. Focus group: Which roles/functions will be affected?

4. Competency model: What new competencies will be needed?

5. Reskilling: Who has the potential to develop these new competencies – and who doesn’t? Who should/could remain in their current role?

6. ROI: What would the reorganization cost? And how long would it take for which scenario to pay off against the ‚business-as-usual‘ and against the ‚immediate sell-off‘ options?

It took a workshop and a model

For a business unit with over 1,000 employees, it makes no sense to deal with the whole thing in a one-time workshop in purely qualitative terms, with ‚sticking cards on pinboards‘. So we needed a quantitative data model that would allow us to calculate such scenarios in order to get exact figures for the target profiles. We then also realized that we could do a ‚profile matching‚ to find out which employee groups we would have to address with which measures. Today, you might call this ‚analytic decision making‚. And we quickly came up with a proud name for the process: ‚Strategic Workforce Planning‚. Finally, we in HR were on the right track strategically (that is, not just running after) – and secondly, we were finally dealing with business-relevant data and planning and not just headcounts or payrolls. In addition, we bought a tool from a large management consultancy that was still being set up in ACCEESS at the time – and of course the management consultancy plus consultants at the same time.

Many parameters – many trends – many scenarios

I will spare you the details of the workshop at the time and summarize the result: it was quite a disaster and almost ended in a conflict with management. Why? Quite simply: if you want to build a data model that calculates scenarios with so many parameters, you need very precise parameter data from the business. What exactly do the future roles look like? What competencies are needed in these roles? When exactly will which innovation come along and replace the old one in the market? And a few internal data are also needed: age structure of employees, skills, fluctuation now and in the future, level of training, mobility between locations, etc. We were in the same situation as the climate researchers: an equation with so many parameters quickly becomes exponential if you tweak a few parameters. In other words, depending on how you look at it, you either come up with ‚we no longer need to hire anyone‚ or ‚we have to hire 20% new employees per year just to maintain our workforce in five years‚. In summary, the equation had too many unknowns to be able to provide scenarios with mathematical accuracy, down to roles and skills. In particular, the business managers could not say exactly when which scenario would actually come into play and which skills a role would then really need. Even the planning data that was given to the board of directors for business planning each year was suddenly no longer as reliable. This causes frustration in a workshop like this! And you have little confidence in the scenarios when it really comes to deriving expensive measures.

Meanwhile (15 years later!), there are more professional tools available (e.g. from Dynaplan) that can do a lot more. In the last few months, I have had the opportunity to support two such projects for customers again. The problems remained similar: a great many parameters and a great many uncertain scenarios that can arise when modelling the future. And an event like Covid-19 can quickly knock such a model on the head.

Makes strategic workforce planning pointless, then?

Does that mean that the whole world is becoming data-driven and analytical, and only we in HR can’t participate because our parameters are too soft, too complex and there are too many dependencies on external factors? I wouldn’t go that far! On the contrary. Seen from a distance, the whole thing actually made a lot of sense. Apart from the frustration of an unsatisfactory and unclear workshop result, there were a whole series of insights for all participants:

- A much clearer feeling for the different scenarios that are even conceivable.

- What complex dependencies and parameters exist and have an influence.

- What dramatic changes could occur in about 5-10 years if the fluctuation rate were 10% (as is common in China) instead of 2% (as it is in our company), for example. That we didn’t know exactly what skills were in the minds of our employees – who had which skills and who would be able to muster how much energy to make a major leap forward in a new technology, for example.

- In retrospect, it turned out that these scenarios were not so bad in their basic tendency. With a little more research, more could have been done. Not a workshop – but a project.

- That continuous collaboration and focused discussion between HR and management is urgently needed.

And something else interesting happened:

word has spread about the scenarios we had developed! Employees have taken this as an opportunity to think about which film they actually want to be in. For example:

‚I’m 55 years old – I’m still riding this wave of technology to the end of my professional life. I’m doing a little more training, but I’m not making any more quantum leaps. I would also let myself be sold – I go where my core competence is core business‘.

But also:

“I’m 35 years old and I want off this sinking ship, which is only going to sink further in the long term. I’m interested in new remote technologies anyway. I want to continue my education and take the next S-curve with me. I’m willing to make sacrifices to do that, to change companies or move.”

Without these scenarios, which we discussed and went through in detail, we would never have been able to have these discussions properly. The future roles that were the subject of much tension and uncertainty in the workshop were also very useful. The employees knew:

‚It’s not going to be exactly like that – but this new role seems at least plausible and attractive enough for me to use it as a rough guide. I know what I have to do to get there‘.

Paths into the future

The different scenarios played out in the workshop were also very useful: they looked like paths in fresh snow. They invite you to follow them mentally – as different possible paths into a future, as options for thinking yourself and your own biography into these scenarios and making personal decisions. It’s as if a piece of the fog lifts and a range of possible options open up. I’ll give away the result too: we sold the business unit to an IT provider at some point. And 15 years later, the business and some names that I know still exist there. Many of our colleagues at the time have made careers in the new fields of technology – even without us having planned it out for them in detail. So the plans developed a dynamic all on their own.

A completely different approach: job-specific scenarios

A few months ago, I met an interesting young scientist named Dr. Jakob Mainert. He has developed a method he calls ‚Cognitive Lense‚. It classifies job profiles of all kinds according to two fundamental dimensions of a matrix that he has developed using factor analysis from parameters of digitizable skills. Within this matrix, each individual activity of a role can be examined according to its ‚digitizable portions‘. This can also be done in a job query and a workshop – but every employee can also do it themselves. The activities that represent economically ‚survivable‚, purely human core competencies can be expanded and further developed. Others can be actively outsourced, bundled, outsourced, etc. This creates an individual, but also an overall picture of an organization. This inductive approach is a smaller alternative to the more deductive, business-strategy-derived ‚Strategic Workforce Planning‘. It does not take into account all business aspects – in this respect it is not complete because it is inductive, but it still provides clarity about the effects of different digitalization technologies on individual jobs. And this method also has an interesting self-referential effect on employees: as soon as the method is presented, the participants/listeners start to go through their own activities: ‚What of what I do could a machine do?‘

Workforce transformation – an interim conclusion

1. Regardless of whether you choose a deductive or an inductive approach to dealing with the question of the survivability of a role, function or task, it always has a systemic effect on the actions of everyone involved. It trains and shapes the thinking of those involved.

2. If you want to calculate real quantitative scenarios, you need really good data: We have many more options available to us today than we used to – for example, there are companies like HR Forecast that can use AI to distill large amounts of data from a data pool or from job ads on the internet in a cost-effective way to create answers, for example, based on skills. But you really need solid scenarios that allow you to omit parameters, even in models, to simplify the world sufficiently. These are more likely to arise in the context of a project and that requires solid methodology.

3. It is an excellent exercise for every HR manager to work through a scenario project like this together with their business managers. Afterwards, they often speak a common language of change and their thought patterns begin to synchronize. It strengthens their own role and relationship.

4. Most important point: Not everything can be planned exactly mathematically in such scenarios – no matter how seductive consulting projects sometimes sound. But:

a) The basic direction of the scenarios is usually correct if the trends and parameters have been sufficiently researched and discussed.

b) It is easy to derive basic strategies for HR from them, such as a new competency model, new role profiles or a training program.

c) You can also further develop such a project into a participatory change project: sharing the results with employees will encourage them to get on board.

Workforce transformation is more than just planning

A classic strategy project can sometimes be developed behind closed doors and produce good results with just a few participants. Workforce transformation in the broader sense, however, requires a much more comprehensive approach due to the large number of organization-specific parameters. If you want to ensure that this approach is truly viable for the organization, it is more of an expedition into an uncertain future that is, however, becoming more and more concrete. A journey with imponderables and possible setbacks for which you have to be prepared – for example, with a broad skills profile. Because it involves a large part of the organization, there are usually a large number of stakeholders who are affected. The more you involve employees in this journey planning, the more effectively you can use the energy of those involved in a positive way. After all, who doesn’t want to think about their own job risks, development and career opportunities? Maintaining employability is a strong intrinsic motivator to go the extra mile. This process sometimes also reveals bitter truths. For example, that tasks or stages of the value chain cannot be kept profitable in the long term.

Planning transformation in good time is a responsibility

People and organizations often develop forces to protect themselves from such structural change or simply to lie in their pockets. We experience this ourselves in many industries or at the macro-social level – whether it is coal-fired power generation, drive technologies in automotive engineering or our financial industry. The threat of job losses is the strongest lobbying tool for protectionism and subsidies. There are also forces at work in companies that work to maintain structures and status. In some companies, this also includes the works council. However, in my experience, the more closely you involve works councils and employees in such planning and scenarios, the more they recognize the systemic connections and often change from being obstructionists to protagonists. This creates a spirit of optimism that can be put to good use.

In holistic workforce management projects, there are not only ‚push‘ options but also many ‚pull‘ options that can be used to involve employees in future scenarios and not have to leave them to the wild market forces later on. That’s what sustainability means to me – you could also call it a duty of care. We should also embrace the principle at a socio-political level that it is more socially responsible to drive forward foreseeable changes actively and transparently, thus giving people the opportunity to adapt actively and personally in good time, than to try in vain to stop structural change. Seen in this light, companies that engage in workforce transformation are also performing an important social function.